|

Map of Minnesota legislative districts from the Iowa border up through the Fargo and Duluth areas (link)

|

A couple election cycles ago, I focused some of my frustrations with the current political climate by looking up districts along existing and planned passenger rail lines in Minnesota, to help guide my donations. Early voting has begun for the August 13th primary in the state, so it's time to update and share some of that.

Of course, possible corridors run through almost the entire state, so taking a broad approach doesn't necessarily help filter down the choices very much, but looking at one or two corridors at a time is useful. Plus, looking along rail lines helps pull some focus away from Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Twin Cities suburbs—an area with a more active political scene, often to the detriment of outstate races that deserve support too.

I'm focusing here on two main routes, the combined Northstar and Amtrak corridor from Minneapolis through Big Lake and St. Cloud to up to Fargo–Moorhead, and the Northern Lights Express corridor which branches off in Coon Rapids and heads north through Cambridge and Hinckley to reach Duluth, and once had plans for a commuter rail line on the southern part of the corridor as well.

I hate to have to just go through this list and give blanket DFL (Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party) endorsements, since I really do like to believe in the ideals of politics and that people of differing viewpoints can work together to find solutions. We're unfortunately in a state of affairs where Republicans are acting out of spite and malice, cutting programs and services that help people while trying to upend democracy as we know it, and cement a power structure that will make them impossible to oust from office through ordinary means. Democrats certainly aren't immune to making bad choices, but the differences are night and day right now.

There certainly have been Republican politicians who are advocates of passenger rail, and who have fought to keep current lines in operation. The United States has done a far better job of maintaining Amtrak service than Canada has with Via Rail, for instance, which has shrunk dramatically since its inception. However, they still balk more readily at following through to pay for expansion, so intercity rail has been stuck in doldrums for a long time, even as shorter-distance rail transit has generally expanded. So, my lists below will mainly be giving information on DFL candidates.

I've only had time to look through House of Representatives candidates for the Minnesota Legislature and U.S. Congress, but anyone able to take the time should look into mayoral, city council, and county elections along these routes as well.

Northstar: Minneapolis to Big Lake, with St. Cloud extension

The Northstar Line is suffering from a lack of political willpower right now (or actively anti-rail sentiment), still operating at a reduced schedule following intense cutbacks from the COVID pandemic. It's been falsely labeled as a poor performer from the beginning of operation, when it was given a schedule that made it virtually impossible to meet the ridership targets necessary to trigger expansion.

It was supposed to have 9 round-trips per day rather than 6. Individual trains have been pretty full, busier than most other commuter lines in the the country, but the limited schedule has meant the ridership with ⅔ of the intended schedule has reached ⅔ of the intended target. It should be given a proper schedule and be expanded to St. Cloud.

BNSF Railway expanded double-tracking in the corridor about a decade ago, and Amtrak is rebuilding the station platform in St. Cloud to meet current ADA requirements, so the threshold for what's needed to get trains running there should be low. Host railroads for passenger projects always say that they need investment in physical infrastructure in order to maintain their vague notions of "capacity," but a double-track mainline like what they have should be capable of very frequent trains. Some investment will be needed, but it will be pocket change compared to the amount spent on streets and highways in Minnesota each year.

Minnesota House districts

Northstar currently runs through MN House districts 59B, 60A, 39A, 34B, 35B, 35A, 31A, 30B, and 27A. There are no stops in 60A, 34B, or 35B, although the latter two would likely share a Foley Boulevard station in Coon Rapids if that ever comes about.

Extending service northwest from Big Lake would go through Becker and Clear Lake in 27A to St. Cloud in 14B (hard to say if both Becker and Clear Lake would get future stations, but Becker would almost certainly get one). I'll include district 14A as well, which isn't on the rail line but covers much of St. Cloud and has an edge only blocks away from the Amtrak station there.

Minnesota House districts along the Northstar line and proposed extension to St. Cloud

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

| 59B | Minneapolis (Target Field station)

| DFL

| Esther Agbaje | Esther Agbaje | 97.0% |

| 60A1 | Minneapolis

| DFL

| Sydney Jordan | Sydney Jordan | 73.9% |

| 39A | Fridley (station), Hilltop, Spring Lake Park

| DFL

| Erin Koegel

| Erin Koegel | 26.7% |

| 34B1,2 | Coon Rapids, Brooklyn Park | DFL

| Melissa Hortman

| Melissa Hortman | 25.1%

|

| 35B1,2 | Coon Rapids, Andover

| DFL

| Jerry Newton3

| Kari Rehrauer | 1.3%

|

| 35A | Coon Rapids (station), Anoka (station)

| DFL

| Zack Stephenson | Zack Stephenson | 4.9%

|

| 31A | Ramsey (station)

| R

| Harry Niska

| Dara Grimmer

| -19.1%

|

| 30B | Elk River (station)

| R

| Paul Novotny

| Paul Bolin | -31.2%

|

| 27A | Big Lake (station), Becker, Clear Lake

| R

| Shane Mekeland

| Kathryn A. Geary

| -41.9%

|

| 14B4 | St. Cloud (station)

| DFL

| Dan Wolgamott

| Dan Wolgamott

| 3.7%

|

| 14A | St. Cloud, Waite Park, St. Joseph

| R

| Bernie Perryman

| Abdi Daisane

| -1.3%

|

1Tracks pass through this district, but no stations exist there

2Coon Rapids – Foley Boulevard station would be on the border of districts 34B and 35B

3Newton is retiring in 35B and has endorsed Rehrauer

4St. Cloud is served by Amtrak, but not Northstar

State house seats can swing pretty wildly from election to election, so it's hard to say which of these are really "safe" in either direction. I'd most readily recommend donating in the races for districts 35A, 35B, 14A, and 14B. Dan Wolgamott in St. Cloud has been a significant proponent of Northstar expansion, and it wold be great to flip the 14A seat in St. Cloud in order to build a stronger base of support there.

It's a shame that district 27A's DFL candidate Kathryn (Kathy?) Geary doesn't have a website that I could find, since that district could potentially gain two new stations if the line was extended. Aside from 14A in St. Cloud, donating to Dara Grimmer in 31A is your next best bet to flip a seat to DFL, followed by supporting Paul Bolin in 30B.

As of right now, cities with Northstar stations only see three trains inbound to Minneapolis each morning with one outbound, then the opposite in the evening, and the line currently only has weekday service. This needs to at least be expanded back to the pre-pandemic service level, and more trips need to be added midday and in the evening to allow people to ride who aren't just commuting downtown for a 9–5 job. St. Cloud should also get more daily Amtrak service, which I'll talk about below.

U.S. House districts

Zooming out, Northstar operates in U.S. House districts 5, 3, and 6:

U.S. House districts along the Northstar line and proposed extension to St. Cloud

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

| 5 | Minneapolis, Fridley

| DFL

| Ilhan Omar

| Ilhan Omar

| 49.8% |

| 3 | Coon Rapids, Anoka, Ramsey (south of station), western suburbs

| DFL

| Dean Phillips

| Kelly Morrison

| 19.2% |

| 6 | Ramsey, Elk River, Big Lake, Becker, Clear Lake, St. Cloud, northern/western exurbs

| R

| Tom Emmer

| Jeanne Hendricks

| -24.2%

|

Ilhan Omar is facing an opponent in this year's primary (actually multiple, although two of them didn't provide any website), and she can use support for that now even though the DFL candidate is a shoo-in for the general election in November. Early in-person and voting by mail has already begun, and the primary ends August 13th.

Dean Phillips is unable to run this year because he entered the Democratic presidential primary race, and Minnesota doesn't allow people to run for multiple offices at the same time. Kelly Morrison is the endorsed candidate instead. I'm not sure how suburbs will swing this year, so I'm sure she could use support too.

Jeanne Hendricks also has an opponent in the primary, but Jeanne is the one that gained the DFL endorsement through the caucus system. Dan Wolgamott and Abdi Daisane of St. Cloud have been actively campaigning with her. That general election race is a bit of a long shot, but I have no idea how things will play out this year.

The current Republican-held U.S. House is trying again to cut funding to Amtrak and other programs intended to expand passenger rail in the country—something that has been deeply under-funded for decades—while continuing to boost more heavily-polluting highway and airport expansion instead. So flipping that chamber to Democrats would make it much easier to finally grow new intercity services again.

Amtrak to Fargo–Moorhead

One of the highest priorities for expanding rail service in Minnesota is adding a daytime Amtrak train from the Twin Cities to Fargo. This would overlay the existing Empire Builder service, and both would ideally stop at a couple of stations served by Northstar. St. Cloud is the obvious shared stop if Northstar can be extended there, and there are multiple options in the Twin Cities, including Target Field in Minneapolis, Fridley station, or the long-proposed Foley Boulevard station in Coon Rapids.

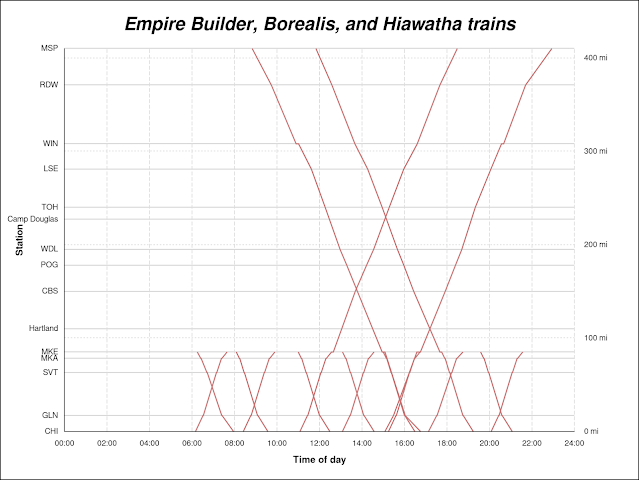

|

Partial schedule for the Empire Builder showing late-night and early morning departures in St. Cloud, Staples, Detroit Lakes, and Fargo. These areas deserve daytime service too, and need political support for additional train service (trimmed from full PDF).

|

Aside from the current station in St. Cloud, the Empire Builder also stops in Staples, Detroit Lakes, and Fargo (across the river from Moorhead, and the two cities share a local bus system).

Amtrak service to Fargo might continue westward from there through the state as a revival of the old North Coast Hiawatha service and its Northern Pacific Railway predecessors, but it's possible that could take a different route by running westward from Minneapolis to Willmar and then north to Fargo.

Minnesota House districts

The Empire Builder continues beyond St. Cloud through Minnesota House districts: 13B, 10B, 10A, 5B, 9B, 5A, 4B, and 4A before crossing into North Dakota.

Minnesota House districts along the Empire Builder route north and west of St. Cloud

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

13B

| Sartell, Sauk Rapids

| R

| Tim O'Driscoll

| Dusty Bolstad

| -33.5% |

10B

| Rice, Milaca

| R

| Isaac Schultz

| JoEllen Burns

| -57.3% |

10A

| Little Falls, Aitkin

| R

| Ron Kresha

| Julia Samsal Hipp

| -92.6% |

5B

| Staples (station), Long Prairie, Wadena

| R

| Mike Wiener

| Gregg Hendrickson

| -51.0% |

9B

| New York Mills, Perham

| R

| Tom Murphy

| Jason Satter

| -40.8% |

5A

| Frazee, Park Rapids

| R

| Krista Knudsen

| Brian Hobson

| -41.0% |

4B

| Detroit Lakes (station), Dilworth

| R

| Jim Joy

| Thaddeus Laugisch

| -25.9% |

4A

| Moorhead

| DFL

| Heather Keeler

| Heather Keeler

| 17.3% |

Those are some very tough-looking numbers, but many of them may not really be as bad as they look at first glance.

For the purposes of this list, Sauk Rapids and Sartell are close enough to directly benefit from expanded service at St. Cloud station, especially since they're also in the St. Cloud Metro Bus network. Maybe someone can help Dusty Bolstad fill out her website, which looks very sparse.

It's unfortunate that I can't find much information on JoEllen Burns in 10B. Ages ago, Northstar was supposedly being studied to potentially reach Rice, but who knows how realistic that ever was. It could have been a mini commuter extension for people wanting to get into St. Cloud, on top of the service for everyone headed toward Minneapolis. This looks like it's the most rural district on the list. I really hate

to see the urban/rural divide play out with drastic political splits, since I think we do

have a responsibility to help people live better lives wherever they

are. The line of the Empire Builder passes through but doesn't stop anywhere in 10B, although the southwest corner of the district isn't far from St. Cloud, so expanded Amtrak and Northstar service would still help people in the district.

10A looks especially tough at first glance, but Ron Kresha ran unopposed in 2022. He's facing a primary opponent this year, but I can't evaluate either of their chances since my values don't align with theirs. Little Falls would be a great place to add another station along the line to Fargo since it has a larger population than Staples, and is now up above 9,000 residents. Little Falls would be a great access point for people driving down from Brainerd. Julia Hipp is running on the DFL side in that race. Help her build up a foothold in Little Falls and the other larger towns in the district.

Gregg Hendrickson previously ran against Mike Wiener in 2022, but under the Independence-Alliance Party, a descendant of the state Reform party that Jesse Ventura ran under back in 1998. There wasn't a DFL candidate that year, so perhaps people were anxious to opt for a third party. Ventura was a champion for getting light rail and commuter rail started in Minnesota, so Hendrickson could try and build on that legacy as he runs as a DFLer this time around. Staples station is in the district and would benefit from a daytime train instead of the 2 am and 5:30 am arrivals it sees today.

District 5A is another of the most rural ones along the line. The Empire Builder runs through Frazee on the western edge of the district, but does not stop there. Staples is not far away from it, though. Knudsen and Hobson previously ran against each other in 2022.

4B is home to Detroit Lakes and the station there, and extends west all the way to the North Dakota border, wrapping around but not including Moorhead. Detroit Lakes currently sees the Empire Builder scheduled for about 3 am and 4:30 am, so it would greatly benefit from daytime rail service. Dilworth in the west part of the district is the end of the Staples subdivision that runs from Minneapolis, and there's a large rail yard there.

4A is the final Minnesota House district, where Heather Keeler is the DFL incumbent in Moorhead and is running again. She appears to have had a consistent level of support from the voters, but of course I wouldn't use that an excuse to avoid supporting her this time around. Fargo, right across the Red River of the North from Moorhead, currently has the Empire Builder scheduled for around 3:30 and 4:15 am.

If I had time, I'd cross the river and look at the North Dakota districts too, but I'll have to end there. Getting expanded service in Fargo is very important, since the Fargo–Moorhead area now has more than 260,000 residents. Despite that, the awkward scheduling means it has the third-busiest Amtrak station in North Dakota, even though it's the biggest city and metro in that state.

U.S. House districts

There is one U.S. House district between St. Cloud and Fargo, district 7:

U.S. House districts along the Empire Builder route north and west of St. Cloud

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

| 5 | Detroit Lakes, Staples, Moorhead, Alexandria, Hutchinson, Litchfield, Morris, Marshall, Willmar, etc.

| R

| Michelle Fischbach

| AJ (John) Peters

| -33.9%

to

-39.3% |

Congressional District 7 is huge, larger than 10 states. There was a Legal Marijuana Now candidate in 2022 who likely split some of the electorate, but it's hard to say how much, and the district certainly has a substantial conservative lean.

The district has two stations in it and is close to two others. There are other rail corridors that have been studied to run through here, most prominently running west from Minneapolis through Litchfield (north of Hutchinson) to Willmar, with one branch splitting north to head to Fargo via Morris, and another heading south to Sioux Falls, South Dakota via Marshall (though some plans have that running via Mankato and Worthington instead, which would just barely clip through the southern edge of the district.

Hopefully AJ Peters can make some progress this year.

Northern Lights Express: Minneapolis to Duluth

The long-planned Northern Lights Express would return rail service to Duluth, which previously had Amtrak service until 1985. In addition to the Northstar districts up through Coon Rapids, NLX is planned to run through Minnesota House districts 31B, 27B, 28A, 11B, 11A, and 8A. I included 8B covering the other half of Duluth.

The line would also run through some districts in Wisconsin, including a stop planned for Superior, but I'm not going to investigate that here. At present, it seems the NLX line is only expected to stop in Minneapolis, a suburban station such as Coon Rapids – Foley Boulevard, Cambridge, Hinckley, Superior (WI), and Duluth.

There had been plans for a Bethel corridor commuter service, though despite the name, I think it was intended to run to Cambridge.

Minnesota House districts along the planned Northern Lights Express

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

| 59B | Minneapolis (Target Field station)

| DFL

| Esther Agbaje | Esther Agbaje | 97.0% |

| 60A1 | Minneapolis

| DFL

| Sydney Jordan | Sydney Jordan | 73.9% |

| 39A | Fridley (station), Hilltop, Spring Lake Park

| DFL

| Erin Koegel

| Erin Koegel | 26.7% |

| 34B1,2 | Coon Rapids, Brooklyn Park | DFL

| Melissa Hortman

| Melissa Hortman | 25.1%

|

| 35B1,2 | Coon Rapids, Andover | DFL

| Jerry Newton3

| Kari Rehrauer | 1.3%

|

| 31B1 | Andover, Oak Grove, East Bethel, Ham Lake

| R

| Peggy Scott

| Gadisa Berkessa

| -36.2%

|

| 27B1 | Bethel, Princeton, Zimmerman

| R

| Bryan Lawrence

| Andrew Scouten

| -69.1%

|

28A

| Cambridge, Isanti, North Branch

| R

| Brian Johnson

| Tim Dummer

| -36.1%

|

11B

| Hinckley, Sandstone, Mora, Pine City

| R

| Nathan Nelson

| Eric Olson

| -36.8%

|

11A1

| Cloquet, Esko, Moose Lake

| R

| Jeff Dotseth

| Pete Radosevich

| -2.5%

|

8A

| Duluth (station)

| DFL

| Liz Olson4

| Pete Johnson

| 41.1%

|

8B

| Duluth

| DFL

| Alicia Kozlowski

| Alicia Kozlowski

| 42.2%

|

1Tracks pass through this district, but no stations exist or are planned there

2Coon Rapids – Foley Boulevard station would be on the border of districts 34B and 35B

3Newton is retiring in 35B and has endorsed Rehrauer

4Liz Olson is retiring in 8A, Pete Johnson is DFL-endorsed

I'm fairly surprised by a few of these districts where, since I think DFL candidates underperformed in the last election cycle. They districts between Coon Rapids and Duluth are certainly challenging, but I think there are better prospects there.

At the south end, district 31B has some substantially-sized suburbs, although many of them are roughly 6x6 mile former townships that incorporated as cities, so they have quite low density. Still, when Andover (roughly split in half between 35B and 31B has 32,000 residents and other nearby cities fall in the 8,000 to 15,000 range, there should be more effort put into vying for that district. I don't see a specific website for Gadisa Berkessa, but there are some other search hits. I did find his donation page, though.

Similarly, I don't see clear information on Andrew Scouten for 27B, as there appear to be multiple people by that name. Someone willing to put their feet on the ground in Zimmerman and Princeton would likely improve the odds drastically.

Tim Dummer does have a brief article about himself, but that's about it. Cambridge is a substantial place of about 10,000 residents, so there should be some better effort being done there. He does at least have a donation page.

District 11B is the one that I would have expected to be the most challenging so far, since it appears to be the most rural of the bunch. Mora appears to be the largest city in the district, followed by Pine City, each of which are between 3,000 and 4,000 residents. It's a bit odd that Hinckley has been chosen as a site for a Northern Lights Express stop, but it's close to where the line crosses Interstate 35, and for good or ill, the nearby casino may add a lot of riders too.

I was surprised when pulling up the numbers for District 11A. Unfortunately, it doesn't have any stops on the line, since the tracks veer off into Wisconsin in the southwestern part of it, but Pete Radosevich managed to get within 3% of Jeff Dotseth in 2022. I don't know what he's doing, but it's much better than the other folks along the corridor had been pulling off. The biggest population center is Cloquet, around 12,600 people.

In district 8A, Liz Olson is retiring. There are two Johnsons running in the primary to replace her, but Pete Johnson gained the DFL endorsement and is the only one with a fully-fledged online presence. Duluth has pretty safe seats for DFLers, so it will mostly come down to who wins the primary.

Finally, Alicia Kozlowski is the DFL incumbent in partner district 8B in Duluth.

U.S. House districts

The Northern Lights Express route shares U.S. House districts 5, 3, and 8 with Northstar as it heads north from Minneapolis. The additional U.S. House seat that NLX is planned to reach is Congressional District 8, currently occupied by Pete Stauber

U.S. House districts along the planned Northern Lights Express

| District | Cities | Cur. party | Incumbent | Preferred candidate | 2022 margin |

|---|

| 5 | Minneapolis, Fridley

| DFL

| Ilhan Omar

| Ilhan Omar

| 49.8% |

| 3 | Coon Rapids, Anoka, Ramsey (south of station), western suburbs

| DFL

| Dean Phillips

| Kelly Morrison

| 19.2% |

| 6 | Ramsey, Elk River, Big Lake, Becker, Clear Lake, St. Cloud, northern/western exurbs

| R

| Tom Emmer

| Jeanne Hendricks

| -24.2%

|

| 8 | Duluth, Cambridge, Hinckley, Hibbing, Grand Rapids, Bemidji

| R

| Pete Stauber

| Jennifer Schultz

| -14.5%

|

The 8th district historically had a pretty good DFL tilt on account of the mining activity up on the Iron Range and other blue-collar jobs in the region, but that faded in recent election cycles. Perhaps renewed concerns about labor conditions will bring about a resurgence. Jennifer Schultz ran against Stauber in 2022 and is trying again this year. Both are facing primary challengers, though I imagine both will be in the general election again.

While I could quibble about station locations a lot, the Northern Lights Express route is

planned to have multiple round-trips daily (it should be at least 4, and

I recall as many as 8 being floated in the past), which would massively improve

the ability to get around on rails in the corridor. The rural nature of

the area north of Cambridge is a challenge to being able to reach people

who would need it, but it would be a boon for Duluth and other parts of

northern Minnesota.

Hopefully these lists will help motivate some donations and volunteer effort in favor of candidates who have visions looking toward the future rather than tearing down the world we're trying to build. For my sanity, I'm just hoping to expand our mass transportation system along these routes and get us moving away from the deep car dependency we experience today. Supporting the candidates here is one way to move in that direction.