As I write this, the 2016 Minnesota legislative session is coming to a close, and last-minute discussions are taking place to try and sort out transportation funding. One of the major options is the possibility of a 0.5% metro-area sales tax for transit, an increase from the 0.25% currently collected for the Counties Transit Improvement Board. This is partly to finance the Southwest LRT project, which is currently facing a $135 million funding gap. CTIB currently collects $110 million per year, and the increase would bring the funding level to $280 million annually (if it included all 7 counties rather than the 5 that are currently members).

That's a significant improvement, but still pales in comparison to the annual amount of money put into roadways. In 2015, MnDOT funneled $3.28 billion in funds. That included about $1.3 billion on construction for roads and bridges on the state trunk highway system, plus another $1 billion handed over to counties and cities for the County State-Aid Highway (CSAH) and Municipal State-Aid Street (MSAS) programs.

When discussing transit funding, it's common to get bogged down talking about operational costs, even though that is measuring something completely different than the capital spending that dominates the cost of roadways. MnDOT doesn't actually move anyone—they just provide the infrastructure that allows people to move themselves, mostly in cars that are privately owned. Capital spending by transit agencies tends to be fairly low, and it's often dominated by the cost of vehicles and maintenance facilities, with little left over for any actual infrastructure in the ground. New rail projects have all-inclusive budgets that seem high because they count guideways, vehicles, stations, maintenance facilities (which double as parking for transit vehicles), power supplies, and miscellaneous other items.

Given all of that, it's really unsurprising that the mode share for public transportation is very low across the country, and only modestly better in most larger metro areas. But wow, wouldn't that be different if we balanced the amount of spending between different modes? What if we had the money to fund the tunneled and/or elevated lines that would allow denser parts of the Twin Cities to have good transit service? What if we built on the concept of the metro-area sales tax and took that statewide?

This topic has come up over on the streets.mn forum, with a few different ideas tossed around, and some more thoughts have bubbled up as we now watch Denver open several new lines this year, starting with the new A Line commuter service to their airport.

The Twin Cities region has long struggled to fund desirable projects, and it has been especially difficult to get lines with good routings to serve the densest and most populous parts of our region. Minneapolis, which generates the largest number of transit trips of any city in the metro area, is only expected to be served by a limited number of new light-rail stations on the Blue and Green Line extensions.

Of course, if we had a steady stream of $1 billion per year like the trunk highway system does, what has been impossible in the past due to complex federal funding rules would now be far, far more practical. It would be easier to do the logical thing and upgrade Metro Transit's busiest routes.

If we took the funding stream statewide, it would also help transit service in smaller cities, and could fund the restoration of passenger service on current and former freight rail corridors across the state, not to mention a conversion from diesel power to quieter, cleaner, and more efficient electric power. This would make it so "transit" isn't just something for large cities, but also a system for connecting all corners of the state. Most towns in Minnesota were built up along rail corridors, so it would make sense to link them together again. MnDOT has struggled to make progress on the estimated $95 million second daily train to Chicago, a project that should have been implemented years ago. That project and MnDOT's state rail plan are things that could be built up in no time if we treated public transportation the same way we treat highways.

Denver's metro-area transit system is funded with a 1% sales tax, double what is currently being discussed by legislators. Minnesota has a pretty large economy, with a gross domestic product of $317 billion in 2014. Each percent of sales tax from that year brought in about $740 million in revenue. Surprisingly, my hypothetical target of $1 billion isn't that far off. If we wanted to do this, we could.

Are either of those figures the right amount to spend on public transportation in our state? For our present situation, where highway funding has been leagues ahead of what we've gotten for transit decade after decade, it basically seems too low. We can't flip the switch tonight and have a fully built-out statewide system tomorrow, but with issues like climate change lurking, and a possible flip from growth in the sprawling suburbs back into the city grid, I feel like we need all the investment we can get.

Covering rail projects along the Twin Cities – Milwaukee – Chicago Corridor, and delving into the history of the Hiawathas, Zephyrs, and 400s which raced through this region in excess of 100 mph in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s.

Friday, May 20, 2016

Monday, May 9, 2016

Getting around the block: Metro vs. outstate

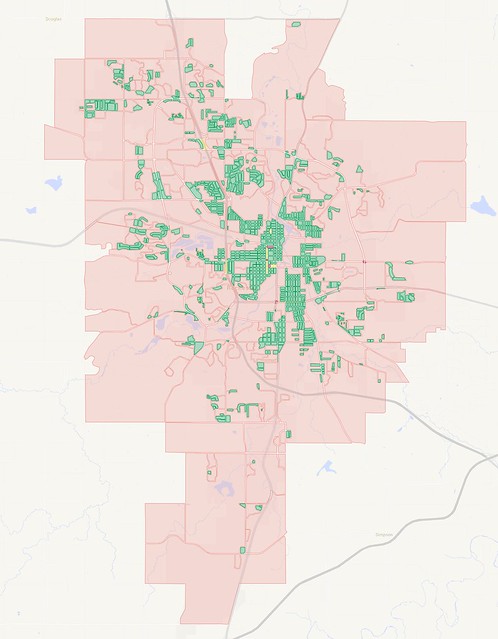

A map of city blocks in Rochester, Minnesota (Click here for full map).

In my last few articles, I've looked at the city block layouts of Minneapolis and Saint Paul (both downtown and citywide) and compared them to a few suburbs. I thought it would be useful to also make some comparisons with cities outside of the metro area, to see what they're like.

Above, I have a map of Rochester, which about 80 miles southeast of the Twin Cities. It's the third-largest city in the state, after Minneapolis and Saint Paul, but is quite a bit smaller than those two. The most recent population estimates put Rochester at about 111,000 residents, which is roughly 27% the size of Minneapolis (pop. 407,000) and 37% the size of Saint Paul (pop. 298,000).

As with previous maps in my series, I've drawn blocks using surface streets (skipping freeways) and given them colors according to size and the presence of one-way streets around the edges. Pink blocks are 15 acres or larger, while green, yellow, and darker red colors are used when blocks are smaller in size. I use green for blocks that can be circled clockwise, while yellow blocks need to be circled counter-clockwise due to one-way streets. Red blocks crop up when one-way streets meet and it's impossible to loop around the block without also including another adjacent block.

The resulting maps tend to show where I find it to be comfortable or uncomfortable to walk around, at least in terms of time and distance. A square block of 15 acres is about 0.6 miles and takes at least 12 minutes to circle on foot, and those figures increase as blocks become longer and thinner, or become twisted around into strange shapes.

I let the blocks continue beyond the city borders until reaching the nearest street roadway that could complete a loop, so the Rochester map bleeds over into unincorporated territory quite a bit.

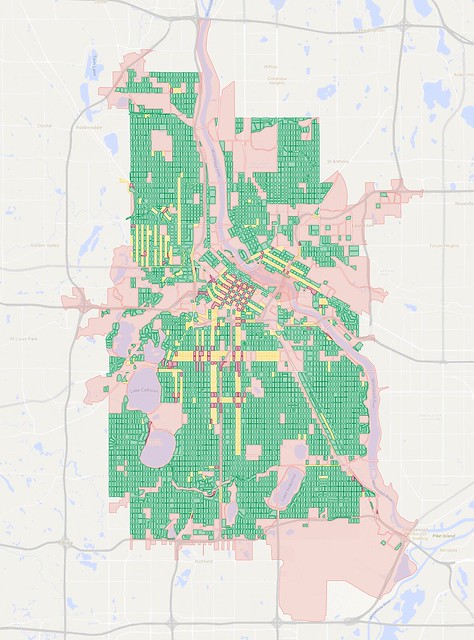

It's useful to compare this map to Minneapolis, which is the most walkable city in the state, along with being the one with the highest transit ridership:

A map of city blocks in Minneapolis. Click here for full map.

It's a pretty stark difference between the two. I traced 4,701 small blocks in Minneapolis compared to 225 large blocks, for a ratio of 21:1. In Rochester, I traced 922 small blocks versus 256 large blocks, for a ratio of just 3.6:1.

Perhaps a better measure is number of blocks per unit area: Minneapolis has about 90 blocks per square mile, while Rochester has less than 22 per square mile. By either measure, Rochester is much more of a sprawling city than Minneapolis, although it's roughly on par with the suburb of Bloomington, which I looked at in my most recent post.

Rochester had a somewhat larger population than Bloomington before suburban-style development took hold, with around 30,000 residents in 1950. That was enough to create a decent gridded area in the city center, even if it was broken up somewhat by a fork of the Zumbro River that flows through town as well as some of the streams that feed it. The city has a reasonable downtown, but suburban-style sprawl has defined most of the growth since 1950.

In fact, one of the more notable monuments to the suburban style of living and working sits on the north side of the city along U.S. Highway 52—the IBM complex designed by architect Eero Saarinen. Both of my parents worked there as I grew up:

IBM's Rochester facility as it appeared around 1958, by Balthazar Korab.

The building's signature blue panels made for an evocative connection between the earth and sky, especially when combined with the landscaping of the site, but the low-slung nature of the two-story complex means that it spreads across a vast area.

It was laid out on a flat plain in a modular design, which made expansion easy, though of course the land area was consumed by parking lots just as rapidly as it was by buildings. The site grew over the years to more than three times the original size (most recently reported at about 3.6 million square feet—a little over half the size of The Pentagon, but more than 2.5x the size of the IDS Center).

The IBM complex as seen from the air around 1958. It has since expanded to about three times the size. Photo by Balthazar Korab.

However, the site is now long past its peak employment, and the amount of hardware manufactured at the site has plummeted. This past week, IBM announced that they would be selling off two-thirds of the site, returning to a footprint similar in scale to what the company originally had in 1958.

A counterpoint to the suburban development by IBM and countless smaller businesses has been the Mayo Clinic's more concentrated development in the city's downtown, though that has unfortunately become surrounded by one of the most distinctly donut-shaped parking craters I've ever come across.

What will Rochester's future hold? There's a lot of momentum for the suburban style of development, especially for housing and retail. Big-box retailers continue to plop buildings down in the middle of empty areas, such as at the "Shoppes on Maine" district on the southern end of town, or the site of the new Menards at the extreme northern edge.

Still, the city's Destination Medical Center project, which aims to build on the success of the Mayo Clinic, is mostly focused on areas in and near downtown. This may restrain sprawling development to some extent, but it seems likely that housing and commercial developers will still seek to spread out onto the cheapest land they can find.

Next, I thought I'd swing my view in the opposite direction and look at Fargo, North Dakota, about 240 miles northwest of the Twin Cities and sitting just on the other side of the Minnesota border:

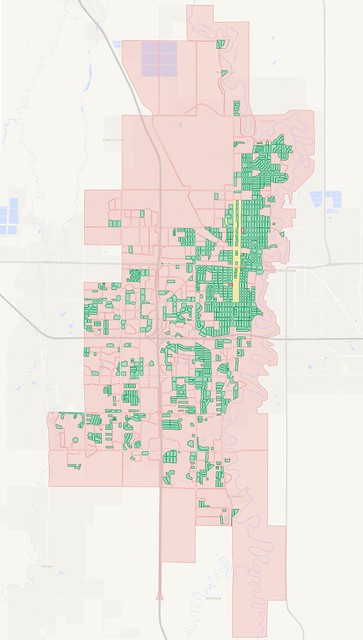

A map of city blocks in Fargo, North Dakota (Click here for full map).

Fargo has an estimated population of about 116,000, just a few thousand larger than Rochester. However, it's squeezed a bit on the west by the suburb of West Fargo and on the east by the Minnesota border and the city of Moorhead. I mapped 1166 blocks and 272 large ones, for a ratio of 4.3:1. That's significantly higher than Rochester's 3.6:1, but still far below Minneapolis's 21:1 or Saint Paul's 14:1.

The street grid spreading out from downtown is more contiguous in Fargo, though there's only one significant river to contend with: The Red River of the North, which defines the border between Minnesota and North Dakota. The grid falls apart as you get close to Hector International Airport in the northwest part of the city, 25th Street heading west, and Interstate 94 heading south.

Rochester and Fargo have been on a similar population trajectory for the past few decades, though Fargo has been developing somewhat more densely. Apartment buildings seem to be much more common in Fargo than in Rochester, though the complexes still tend to be married to large parking lots and are laid out in ways that consume a lot of land, rather than in a more urban pattern facing the street.

Two of BNSF Railway's major routes converge in Fargo and then split apart again on the other side. Despite them passing within blocks of each other near downtown, that part of the city maintains a fairly continuous street grid. However, there is a lot of industrial land centered around the tracks into the western part of the city.

Fargo also sits at the junction of Interstate 94 and I-29, which are also home to many spread-out industrial and commercial sites, including the city's main shopping mall, West Acres (which sits just northwest of the I-94/I-29 interchange). Areas near the interchange also host many hotels, befitting the city's nature as a gateway to the rest of North Dakota.

Further evidence of the city's sprawl is typified by one of my most-/least-favorite ironic place names, lying just southwest of the freeway interchange: The neighborhood of Urban Plains, which is of course neither urban nor plains.

Could Fargo do a proper job of marrying those two ideas in the future? The city's downtown development has been far less intense than in Rochester, but the area's large number of parking lots could give a canvas for a diverse mix of businesses—something different than the medically-focused center that Rochester is trying to make. But for now, just like it's cousin to the southeast, Fargo mostly keeps seeing development pop up well outside the city core.

Both Rochester and Fargo have the population to make them very dynamic places, but the lack of restraint for keeping development compact and connected ends up diffusing a lot of that potential energy. Without big natural barriers, adjacent suburbs, or well-defined urban barriers hemming them in, the cities have had important destinations flung around without any consideration for how people will get there through any means other than by car—something that can't continue to be tolerated in the 21st century. Here's hoping they start changing their plans.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)