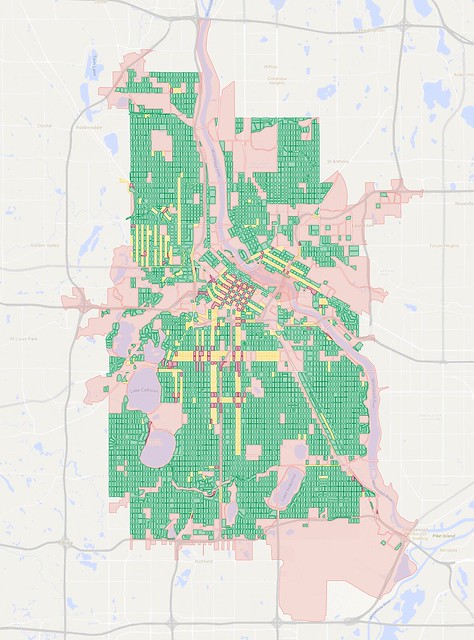

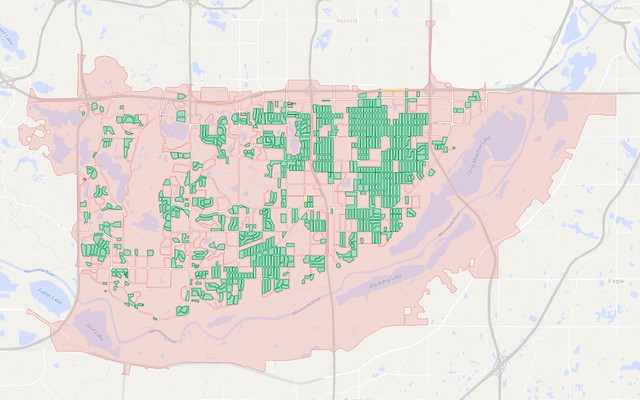

First, let's refresh our memories by taking a look at Minneapolis:

A map of city blocks in Minneapolis. Click here for full map.

In my maps, blocks that are less than 15 acres in size are colored green, yellow, or dark red (the latter two colors help indicate the presence of one-way streets). Blocks of 15 acres and larger are shown in pink. That size is roughly when I find that they become uncomfortable to walk around—these blocks have a circumference of at least 0.6 miles and take at least 12 minutes to circle on foot, and those numbers increase as blocks elongate and morph into strange shapes.

Minneapolis is a city of about 407,000 people, and has been getting built up for more than 150 years. A street grid system has been effective at filling out and giving access to most of the city's developable land. Areas shown in green on the map are generally pretty walkable and bikeable, with typical city blocks around four or five acres in size. Not all areas of the city have good access to things like restaurants, grocery stores, or other shops, but there's generally good connectivity, setting up a nice framework to be built upon.

My Minneapolis map has 4,701 small blocks compared to 225 large ones, for a ratio of about 21:1.

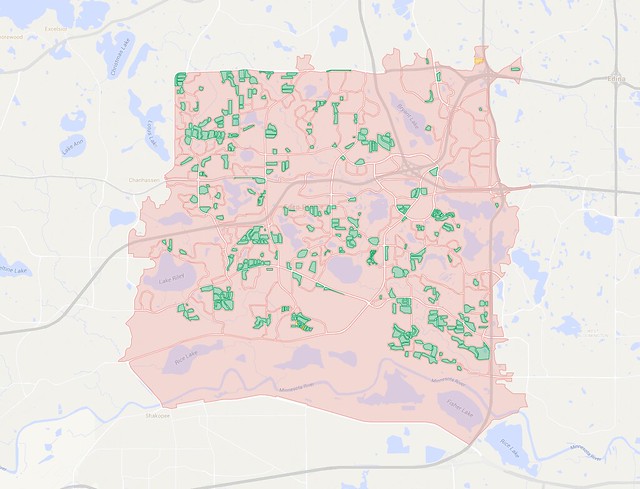

Now let's turn our gaze to Eden Prairie, which hangs off the southwestern edge of the I-494/I-694 beltway. It was incorporated in 1962, and has grown rapidly to become a city of about 63,000 people. An abundance of office parks and retail locations mean that close to 40,000 people work in the city, more than 85% of whom commute from other cities in the metro area. Like Minneapolis, most of the city's developable land has now been divided up into fairly small, privately-owned parcels, so it's almost fully built out:

A map of city blocks in Eden Prairie. Click here for full map.

Um. Yikes!

This map has 328 small blocks and 164 big ones—a ratio of just 2:1, or less than one-tenth the small:big block ratio for Minneapolis.

In a word, this is sprawl. There's a lot more stuff in Eden Prairie than what that map shows, but it's arranged in ways that waste land and make it extremely difficult to get around by any means other than driving. Let's zoom in on a section near Baker Road and Valley View Road to get a better look at what's going on:

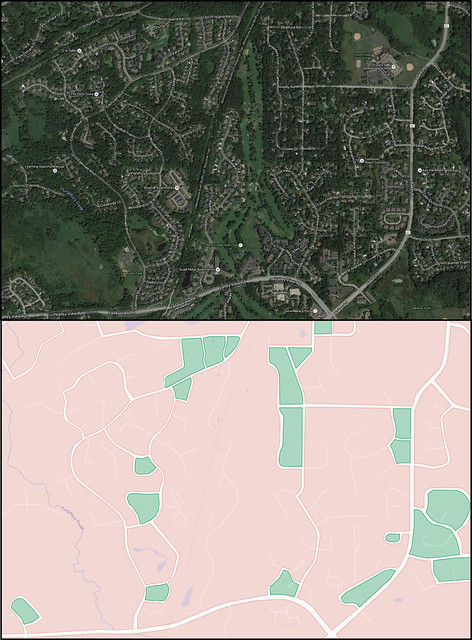

Comparing an aerial view of Eden Prairie to a map only showing city blocks.

This comparison image shows how the suburb's dead-end streets and cul-de-sacs fill up space but don't really contribute to street connectivity. Tracing only the block edge filters out most of the streets that are mere fingers into larger areas of land. The gaps between blocks mostly show through streets, though sometimes blocks exist in small pods that are entirely encircled by a larger block except for a single road to access them.

This map highlights how suburbs' heavy reliance on cul-de-sacs, pod-style development, and hierarchical road systems is bad for walkability and bikeability, and it isn't good for car traffic either.

Do you remember how busy things were at polling places on caucus night this year? My caucus site in Saint Paul was at a nearby school less than a mile away, and I was able to walk there in 15 minutes. While a lot of other people drove, the school I went to was surrounded by a pretty good street grid to walk, bike, and drive on. I'm sure there was some frustration with parking, but there were plenty of open spaces on nearby streets as long as people were willing to walk a couple blocks.

In Eden Prairie, by contrast, a much higher proportion of people had to drive to their caucus sites, and the limited number of alternate routes created cases where the traffic stretched on for long distances—perhaps miles:

The sparse road system in suburbs like Eden Prairie funnels traffic onto the few through streets that remain. A system of small streets connected to feeder streets leading to main arterial roads can create traffic jams that could be sopped up by the grid in more traditional neighborhoods.

The limited number of through routes also creates huge problems for transit planners. Buses operate most effectively when they can run on relatively straight routes to and through mixed-use zones. They can only pick up and drop off passengers along the edges of these blocks, unless a special right-of-way or station is built. Buses that run along the freeway can't stop wherever they want—they have to exit the freeway either on a normal off-ramp or using special bus-only access.

Finding a relatively straight route that manages to hit walkable pockets while also reaching relatively dense areas of population and useful destinations is difficult or impossible with this street layout.

In some cases, there are bicycle and pedestrian paths that break blocks up into smaller areas, but they aren't consistently in place from neighborhood to neighborhood. Single-use zoning is the norm, with residential, commercial, and retail spaces kept segregated from one another, so most paths don't really take you anywhere other than the local neighborhood. Such paths may be nice for recreation, but they aren't able to provide a suitable alternative to getting around the city by car.

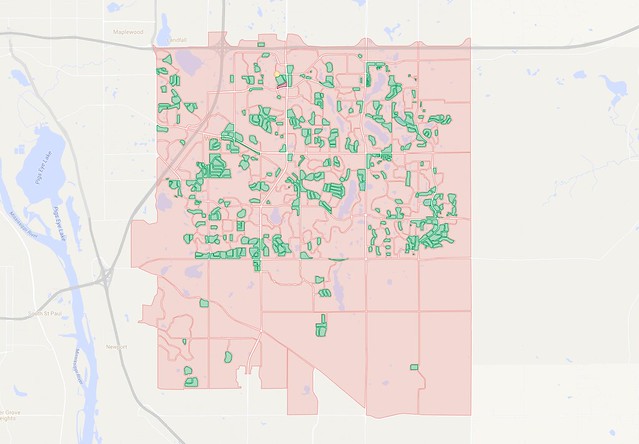

Alright, enough picking on Eden Prairie. Let's find another point of comparison. How about Woodbury, a somewhat more populated suburb of about 67,000 that lies just one mile outside the city limits of Saint Paul:

A map of city blocks in Woodbury. Click here for full map.

Oof.

Okay, by my measurement, there are 377 small blocks in Woodbury and 200 big blocks, for a ratio of about 1.9:1. That's slightly worse than Eden Prairie, though Woodbury's development remains somewhat restricted by the Metropolitan Council's MUSA urban boundary line. A fair amount of the southern and extreme eastern parts of Woodbury is still farmland, so there's some potential for the ratio of big blocks and small blocks to improve before it gets fully built-out, but only slightly if future development continues in the same way as what has preceded it. The area that has developed within the MUSA boundary seems a little denser than Eden Prairie, but not by much.

Both of these cities have completely rejected the street grid, and there's hardly a straight line to be found anywhere within them, with the exception of section line roads roughly one every mile in Woodbury. (They had little impact on the layout of neighborhood streets between them, though.)

Alright, let's try and find a suburb that's a little more ordered in its development. How about Bloomington, which lies just east of Eden Prairie. It has about 86,000 residents and is duking it out with Duluth for the rank of fourth-largest city in the state:

A map of city blocks in Bloomington. Click here for full map.

Aha! Here we have found something of a "missing link" in the transition between cities and suburbs in our metro area. Bloomington is technically an older city in the metro area, as it was incorporated in 1858. However, the number of people living there grew slowly until just after World War II. The population jumped from 3,600 to 9,900 between 1940 and 1950, then exploded to more than 50,000 in 1960 before leveling off at about 82,000 around 1970.

Bloomington lies south of Minneapolis and the inner-ring suburb of Richfield. The Minneapolis street grids extends through Richfield and is present in parts of Bloomington, particularly between Interstate 35W and Cedar Avenue (Minnesota State Highway 77). However, the grid is much more fragmented in Bloomington, and many blocks are considerably larger—essentially two to four Minneapolis-sized blocks merged together.

There's a certain logic to that, since the lot sizes for individual homes also grew as development moved pushed south and west through Bloomington. The most common residential lot size in Minneapolis is about one-eighth of an acre, while houses in Bloomington are typically on lots about two or three times that size. If a block size that formerly contained 30 homes could now only hold 15 or 10, it might make sense to bump up block sizes by a corresponding amount, in order to avoid creating too much infrastructure for too few people.

That alone might not have been so bad, but the city block structure also began to twist, turn, and break apart first as curving streets and then cul-de-sacs became fashionable among developers in the post-war era.

Lot sizes for commercial and industrial businesses also grew, and retailers were often concentrated into strip malls or shopping centers, all of which were major contributors to the weakening of the street grid. Even though many businesses have the same or similar amounts of square footage as comparable ones on smaller parcels in the core cities, they're separated into single-use buildings and surrounded by parking lots.

All of this helps explain why so few people walk, bike, and take transit in the suburbs as compared to Minneapolis. The idea of a standard city block is completely alien in these areas, and people can live their whole lives without really understanding what it's like to live in a true neighborhood where it's possible to live, work, eat, shop, and do most other things without needing to get on a highway.

As Nick Magrino noted in his Measuring the Metro Area and Getting Real with the Map piece, only the core cities and a limited set of the suburbs can be considered "urban" in a traditional sense. Without the framework of a tight grid or other small-block layout, it becomes nearly impossible to meet or even set meaningful goals for increasing mode share for walking, biking, or taking transit, and it makes it extremely challenging to serve populations like children, the elderly, or those with disabilities who can't move themselves around by car.

While developers have occasionally tried to go back to smaller block sizes in what I like to call "New Urbanish" projects, they are still often isolated in small pods. Going back to the grid is one of the only ways to break developers of their bad habits. But are we already too late?

As a recent (~5 years) convert to the city grid I can't imagine living anywhere else. The idea of having to get in a car for every where you want to go is incredibly depressing to me. I'd say it is too late for the grid in the burbs but that's okay because that is what people want. The supply for the city grid outweighs the demand as evidenced by inexpensive houses in East Saint Paul and North Minneapolis. If people really valued this layout we would be seeing these places gentrify.

ReplyDelete